Driving a Risk-Based Approach to EHS Auditing

Jun 28th, 2016 | By Lawrence Cahill Robert Costello | Category: Auditing

Risk is trying to control something you are powerless over — Eric Clapton

In recent years there has been considerable discussion in the environmental, health and safety (EHS) audit profession about how to apply the concept of risk to an audit program. The theory is that risk-based programs will likely result in a more efficient and effective application of resources and a more targeted focus on truly important issues as opposed to pedantic administrative deficiencies. Historically most of the discussion has centered principally on establishing facility audit frequencies based on risk using factors such as:

- Size of the facility

- Facility location and setting

- Regulatory environment

- Uniqueness of the product

- Complexity of the operation

- Compliance history

- Previous audit results.[1]

It should be noted that there are some trends in the U.S., in particular, that are possibly hindering the movement towards full risk-based programs beyond simply defining audit frequencies based on risk. One of these is the continued growth of EHS regulations in the U.S., driven principally by the fact that in 2016 there are more pages of regulations in the Title 29 (OSHA) and Title 40 (EPA) U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (over 29,000 pages total) than at any time in history. Non-compliance with each and every one of the requirements contained in the codes could carry with it statutory penalties exceeding $50,000 per day per violation plus possible criminal penalties including prison time. Also, according to ENHESA’s 2016 Global EHS Regulatory Forecast posted on their website, the regulatory growth in other parts of the world is beginning to rival that of the U.S.

This increase in the regulatory burden can cause audit program leaders to design programs with a “fail-safe” approach, addressing the universe of regulatory requirements equally, even those of a strictly administrative nature. This in turn has generated automated protocols and processes addressing thousands upon thousands of questions for the auditor to answer, a virtually impossible task; ask anyone who has ever conducted an EHS compliance audit at a major industrial operation located in the United States or in any other part of the developed world for that matter.

Fortunately, there is some potential relief on the horizon. For example, the recent 2015 version of the ISO Environmental Management System Standard (ISO14001:2015) has seemed to reinforce a need for management to focus more closely on identifying and assessing those operations and activities that pose the true significant risks to an organization:

The organization shall establish environmental objectives at relevant functions and levels, taking into account the organization’s significant environmental aspects and associated compliance obligations, and considering its risks and opportunities. (ISO 14001:2015, §6.2.1)

This philosophy feeds quite naturally into the need to develop and implement a risk-based audit program as ISO goes on further to suggest:

The audit programme, and the frequency of internal audits, should be based on the nature of the organization’s operations, in terms of its environmental aspects and potential environmental impacts, risks and opportunities that need to be addressed, the results of previous internal and external audits, and other relevant factors (e.g. changes affecting the organization, monitoring and measurement results and previous emergency situations). (ISO 14004:2015, §9.2)

This brief article describes an approach that can be used by audit program managers and auditors to lift themselves out of the fog of the regulatory morass and better focus on what’s truly important on an EHS audit. This approach not only helps to compare relative risks among differing facilities but will aid in shaping audit teams and defining the audit scope to better address true site and organizational vulnerabilities.

Driving a Risk-based Approach

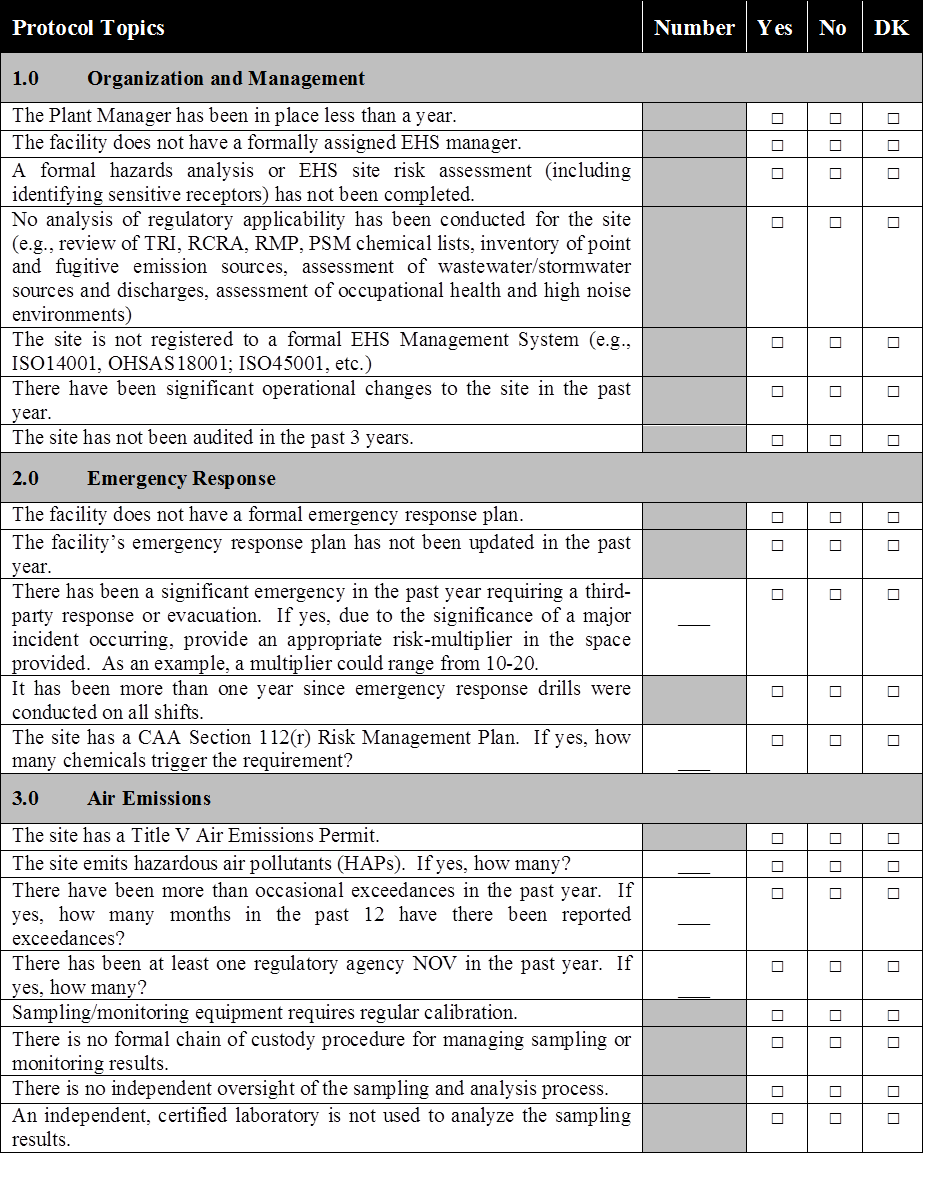

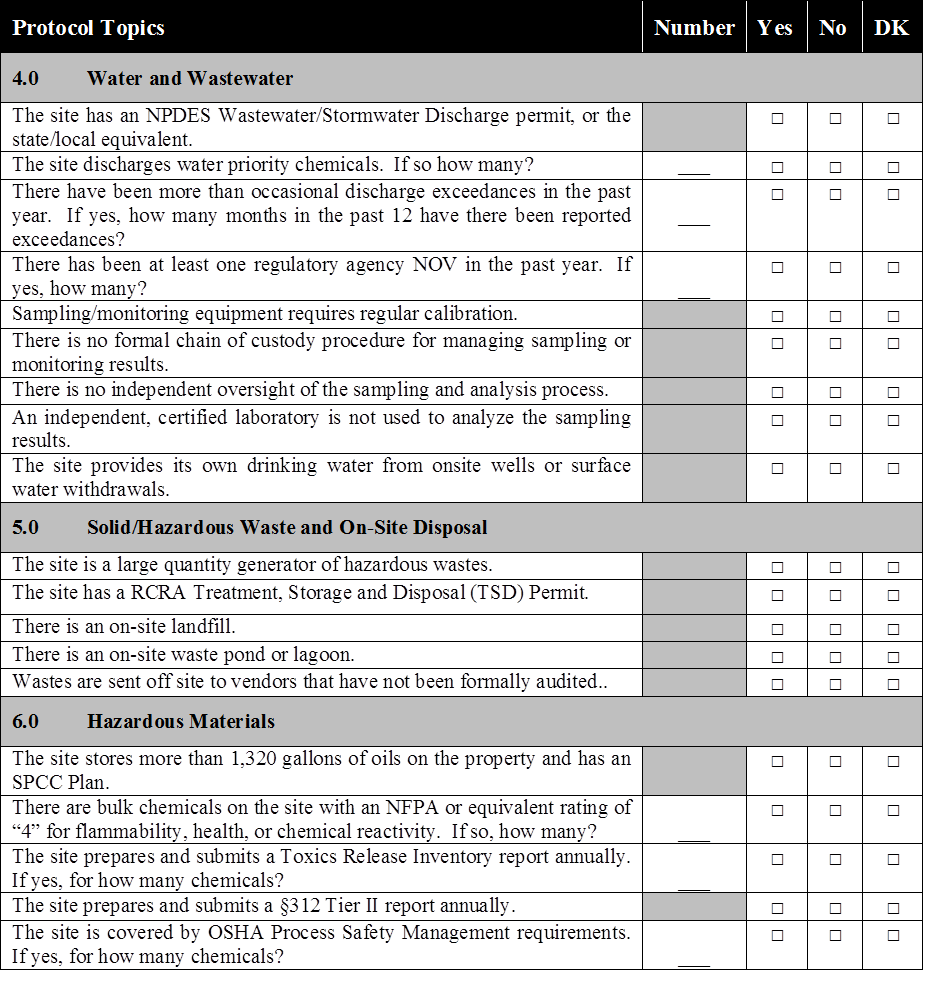

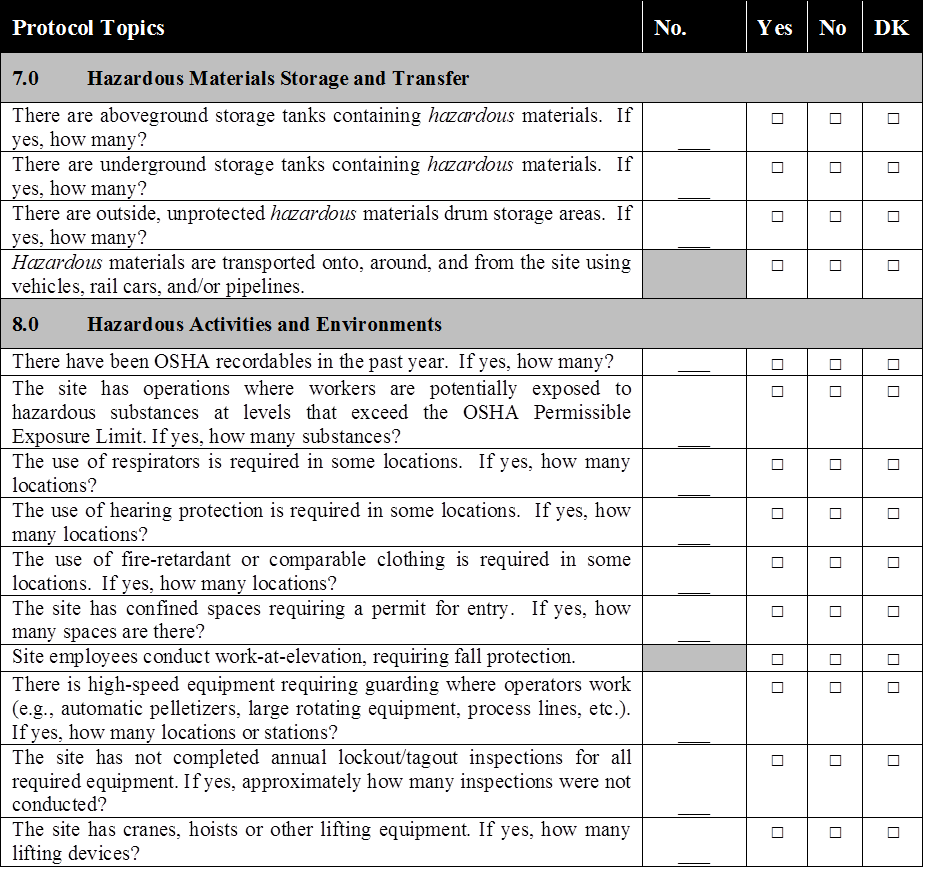

The proposed approach is simple in concept but perhaps a bit more difficult in execution. The idea is to utilize a Facility EHS Risk Profile Protocol similar to the “strawman” provided in the tables below to both help establish an audit frequency for sites but, perhaps more importantly, to allow for the formation of more appropriate audit teams and to drive these teams to focus on the key compliance and performance issues while on site.

The protocol poses a series of statements within eight fundamental protocol topics:

- Organization and management

- Emergency response

- Air emissions

- Water and wastewater

- Solid/hazardous waste and on-site disposal

- Hazardous materials

- Hazardous materials storage and transfer

- Hazardous activities and environments

The protocol is brief, with the responder having to answer each of 53 total statements with a yes (Y), no (N), or don’t know (DK) response. This is only an average of seven statements per topic. The entire protocol can be completed by a knowledgeable site person within one hour, absolute maximum. Where it’s important for an auditor to better understand the relative magnitude of the potential risk for a given topic, a numerical estimate must be provided. For example, this would include the number of:

- Months in the past year with wastewater permit exceedances

- High noise areas requiring hearing protection

- Permitted confined spaces

- Chemicals manufactured, processed, or used subject to Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) reporting

These numbers should be readily available at the site and, if they are not, that alone says something about the site’s EHS management program.

Without being too accusatory, each of the statements attempts to uncover potential risks posed by the elements of that particular topic. For example, is the plant manager new to the job? Has a regulatory applicability study ever been done? What is the recent history of regulatory non-compliances and/or violations and OSHA recordables? Is the process for environmental sampling, including chain of custody and equipment calibration, less than robust? Have there been any historical noise or industrial hygiene surveys? And so forth.

The protocol could be utilized in potentially three different ways: to establish audit frequencies, to form appropriate audit teams, and/or to create audit work plans for the actual audits. These three uses are discussed directly below.

- Establishing audit frequencies. The protocol can be used to score sites based on the risks posed by the activities present. Because of the way the statements are framed, one would assign a score of one point to every “yes” or “don’t know” response and zero to every “no” response. In cases where a numerical estimate is also provided that “1” score would be multiplied by the applicable number. For example, if there are four aboveground storage tanks containing hazardous materials on site, then the score for that element would be “4” (four multiplied by one). A total score is calculated by adding the scores of each individual line. Simple; the higher the score, the greater the potential risk. Subsequently, site scores could be compared to one another to establish audit frequencies based on relative risk.

- Forming appropriate audit teams. Once the protocol is completed by the site and returned to the audit program manager, it can be used to help decide the makeup of the audit team. For example, if the process for wastewater sampling and monitoring equipment calibration is determined to be less than robust and there have been permit exceedances in the past 12 months, the audit program manager might want to add a team member that has some experience in the operations of wastewater treatment plants or an analytical laboratory. Not all EHS auditors have a deep understanding of the issues that affect wastewater treatment effectiveness or the accuracy of sampling and reporting for wastewater discharges. Similarly, if the site is covered by OSHA’s Process Safety Management regulations, the team should probably have an expert in assessing the mechanical integrity of covered critical process equipment. This is not a skill that many traditional auditors possess and, therefore, the topic might receive only a cursory review unless a subject matter expert (SME) is part of the team. (Based on historical incidents, treating mechanical integrity on an EHS audit as just another topic could be a serious oversight.)

- Creating audit work plans. A concern often expressed by executive and line management is that EHS audits have devolved over the years into an exercise that focuses too much on “administrivia.” This should be avoided and can be partly offset by using the completed protocol presented in this article. For example, if the responder confirms that the site is not a Large Quantity Generator of hazardous waste then this topic could be de-emphasized. Or, if respirators are required only once per year during a scheduled maintenance activity for a minor operation this too could be de-emphasized. This de-emphasis (not elimination) might be anathema to some but it’s about time that EHS audits focus on what’s most important to the organization and not be hamstrung by the need to complete a 10,000-question regulatory protocol. Auditors need to get out of their comfort zones and dig deep into those issues that truly could degrade the environment or injure people.

There are potentially several other ways that the protocol and the provided information could be used to manage a risk-based audit program. For example, the data could be rolled up and used to analyze where the company has specific vulnerabilities across businesses and geographies. Focused programs and procedures could be put in place to better manage these vulnerabilities. Exploring these other uses could add value to the tool and ultimately the program.

Closure

Risk-based EHS auditing will no doubt continue to receive increased attention as the profession evolves. The commitment to maintain or even increase audit program resources will always be challenged as executive management looks to reduce operating expenses wherever possible. Use of tools such as the protocol discussed in this article can help to re-engineer audit programs to better focus on issues that are critically important to an organization.

Facility EHS Risk Profile Protocol

About the Authors

Lawrence B. Cahill, CPEA (Master Certification) is a Technical Director with Environmental Resources Management (ERM). He has over 35 years of professional EHS experience with industry and consulting. He is the editor and principal author of the widely used text, Environmental, Health and Safety Audits, 9th Edition and its 2015 follow-up text EHS Audits: A Compendium of Thoughts and Trends, both published by Bernan Press. He has published over 70 articles and has been quoted in numerous publications including the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Mr. Cahill has worked in over 25 countries during his career. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Northeastern University where he was elected to Pi Tau Sigma, the International Mechanical Engineering Honor Society. He also holds an M.S. in Environmental Health Engineering from the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science of Northwestern University, and an MBA from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He is a Certified Professional Environmental Auditor, Master Certification.

Robert J. Costello, PE, Esq., CPEA, is a Partner at ERM in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. He has more than 20 years of professional environmental resource management and consulting experience. Mr. Costello manages global regulatory compliance, management systems, and sustainability assurance programs and typically participates on-site in 30 or more audits and assessments per year. He holds a B.S. in Environmental Engineering from Wilkes University, an M.S. in Environmental Engineering from Syracuse University, and a J.D. from Syracuse University. Mr. Costello is admitted to the bar in Pennsylvania, is a licensed professional engineer in Pennsylvania and Delaware, and is a Certified Professional Environmental Auditor.

Photograph: Check Knowledge by Yaroslav B, Moscow, Russia.

Return to the EHS Journal Home Page

[1] Cahill, L.B., “Using Risk Factors to Determine EHS Audit Frequency,” EHS Journal On-Line, April 23, 20

[…] Driving a Risk-Based Approach to EHS Auditing […]

[…] Driving a Risk-Based Approach to EHS Auditing […]

Great article! Bernardo, a great Colombian auditor simplified it once saying: get up in the helicopter get an overview of the site and look for vulnerabilities. Have a safe 4th of July