Key Performance Indicators for EHS Audit Programs

Oct 17th, 2015 | By Lawrence B. Cahill | Category: Auditing

Introduction and Summary

There continues to be intense discussion in the environmental, health, and safety (EHS) audit community over how to evaluate the performance of audit programs. Senior executives in both private and public sector organizations want to know whether audit programs are meeting expectations and resulting in compliance improvements. Further, they are looking for clear measures that help them make that determination. Unfortunately, all too often the focus is on reporting the total number of findings on audits as a simple and easily understood metric — and it is both of these. But is this metric meaningful?

The short answer to the question is no, principally because all findings are not created equal. For example, as discussed in a previous article by this author, “Let’s say that an audit team finds that a regulatory program does not exist at a site because the site erroneously believes that the program does not apply to them. One finding. A second team visits the site two years later and finds that much work has been undertaken, and the program has been largely implemented. However, there are still four administrative requirements that are not being met completely. Four findings. It’s pretty clear that the one finding on the first audit far outstrips the importance of the four findings on the second audit. Hence, if one were using total number of findings as a measure, the results would be quite misleading.”[i]

As also discussed in the previous article, similar fallacious logic is sometimes applied to other outcomes that might be anticipated by the implementation of an audit program, including a reduction in environmental releases and workplace injuries or improved compliance as defined by a reduction in fines and enforcement actions.[ii] And in fact, even expecting a reduction in the number of overall findings on audits year-on-year can be misleading as well. This is principally due to change, which could include among other factors changes in management at the site, changes in the products manufactured and chemicals used, changes in physical facilities and equipment (e.g., decommissioning and startup of new process equipment); and/or changes in the volume and severity of regulations affecting the site. It’s interesting to note that federal U.S. EHS regulations alone (i.e., Titles 29 and 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations) have increased by over 3,200 pages in the past five years. This has consequences in meeting the goal of full compliance.

If all of the above factors aren’t the best measures of success, how then should one approach this issue of assessing the performance of EHS audit programs? First, it might be valuable to identify the five fundamental questions that one would ask of any audit program in order to assess its effectiveness. They are:

- Has the universe of auditable facilities been identified?

- Are the facility audits being conducted at appropriate frequencies based on the risks posed?

- Are the audits conducted professionally using independent, qualified auditors supported by appropriate audit tools (e.g., protocols, regulatory databases)?

- Are audit reports issued promptly and are the identified audit findings corrected in a timely fashion?

- Is there a sense from the outcomes of the audits that the sites are actually improving?

Defining key performance indicators (KPIs) that would help to answer these questions might go a long way towards understanding the value that an audit program provides. This article attempts to do that by posing a set of eight KPIs, which are summarized along with candidate annual performance metrics, in Table 1 below. Five of the KPIs focus on how well the program is managed and three focus on the actual outcomes of the audits. The remainder of this article explains the nature of each of the KPIs and their metrics in much more detail. The entire set of KPIs can help to answer the question: “Is the audit program meeting its objectives and is it making a difference?”

Table 1: Candidate EHS Audit Program KPI’s and Annual Metrics

Program Management KPI’s

It is critically important that an EHS audit program have a defined and documented set of objectives and that the manager(s) of the program be evaluated against those objectives, if for no other reason than the program’s auditors expect the very same thing from the sites they audit — define the goals, meet the goals.

Discussed below are five KPI’s that are derived from a typical set of objectives for an audit program:

- Conduct the audits as scheduled;

- Assure audit teams consist of trained leaders and members;

- Develop quality audit reports;

- Deliver audits on time; and

- Solicit, evaluate, and act upon feedback from the audited sites.

1. Audits Conducted as Scheduled

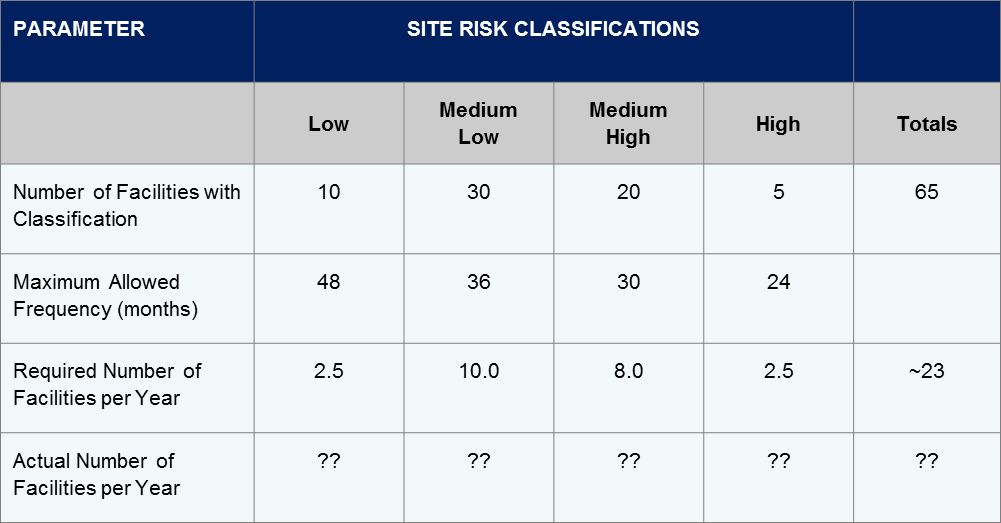

In most organizations an annual schedule of audits for the coming year is developed in the fourth quarter of the preceding year. Schedules are routinely based on general site risk factors, the time since the last audit, success in correcting findings from the previous audit, significant management or process changes since the last audit, etc. An example of how site risk factors might be incorporated into an annual schedule is provided in Table 2. The model’s outcome for this example requires that approximately 23 of the 65 facilities within the auditable universe be audited annually, with separate targets for individual risk classes. This, then, is a number that can be used as a core KPI for the audit program. And as the annual performance metric states, acceptable performance would be having >95% of the scheduled facilities audited, given that achieving 100% of the goal is generally unrealistic due to any number of factors (e.g., divestitures, plant shut downs).

Annual Performance Metric: >95% annual completion rate for the scheduled audits.

Table 2: Number of EHS Evaluations Required Each Year Using a Site Risk Classification Matrix

2. Audit Team Leaders Qualified

“Environmental, health, and safety (EHS) auditing can be a challenging profession. It is fraught with ethical and technical dilemmas, the need to stay technically and functionally competent, and the need to have interpersonal skills and attributes that only Moses possessed. For example, International Organization for Standardization (ISO) auditing guidelines require auditors to be ‘ethical, open-minded, diplomatic, observant, perceptive, versatile, tenacious, decisive, self-reliant, acting with fortitude, open to improvement, culturally sensitive, and collaborative’.[iii] Really, can any one person meet these expectations? Probably not.”[iv]

Very talented and competent individuals don’t always make the best auditors. There are certain skill sets required in auditing that often need to be learned. Thus, audit team leaders and members will typically need a certain amount of training in order to be effective in their role. In most organizations, the minimum expectation is that audit team leaders be certified (e.g., Certified Professional Environmental Auditor [CPEA], Certified Process Safety Auditor [CPSA]), have received specific auditor training, or both. In addition, some companies require that team leaders receive auditor refresher training at least once every three or so years in order to: keep their skills fresh, be made aware of learnings on recent audits, and be updated on developments in generally accepted audit practices (e.g., new ISO standards). The same could be said for audit team members, but in many companies the training requirements are not as strict for them; they rely on the team leaders to lead by example and to mentor team members during the actual audits.

An audit program needs to establish the certification and training requirements for all its auditors, particularly its team leaders. A suitable metric is to require that >90% of audit team leaders be certified and/or trained in auditing. This allows for special circumstances where a technical expert who is not certified or trained might be required to lead a special-purpose audit (e.g., Process Safety Management Mechanical Integrity). Additional requirements can be applied to audit team members but even more flexibility is likely needed for these individuals in order to fill out the audit teams.

Annual Performance Metric: >90% of team leaders certified (e.g., CPEA) and/or received formal auditor initial or refresher training in the past three years.

3. Audit Reports Submitted on Time

Any audit program should have a requirement that draft and final audit reports be delivered within a certain time frame. A typical objective is to issue a draft report within 15 business days and a final report within 30 business days from the last day of the audit. Unfortunately, issuing late audit reports is a chronic issue for many corporate audit programs. There are any number of reasons for this including the following:

- A due-date requirement is not established by the corporate audit procedure so no one is exactly sure when the reports are due.

- The audit program manager fails to track and effectively husband issuance of the reports.

- Because some controversial findings were never resolved during the on-site closing conference, the audited site sits on the draft report and does not respond with comments within the required timeframe.

- In order to be more efficient, an audit team conducts back-to-back-to-back international audits and is unable to devote the needed time while on the trip to writing the individual reports.

- Reports are sent to a “black-hole” legal department. Controversial reports go in but never come out.

- Part-time auditors return to their regular duties and become distracted.

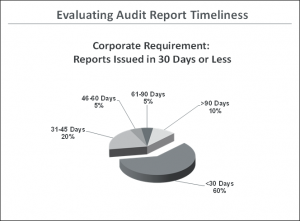

Figure 1 shows an actual evaluation of report issuance for a Fortune 100 company. Note that only 60% of the final audit reports were delivered on time. It turned out that corporate management was indeed concerned about the lack of overall performance but they were even more concerned that 10% of the reports were not issued within 90 days, and in some of these cases, no report was ever issued. Needless to say, corrective actions were taken to improve performance.

Notwithstanding the above sometimes legitimate reasons for late reports, an audit program should be issuing its reports consistent with a prescribed protocol. And the delivery of reports should be a key metric for determining the program’s success. Where reports are never issued or are issued a year or more after the audit or when the principal site staff involved in the audit are no longer working in their previous position, this can really compromise the integrity of the program and its credibility throughout the organization. To be fair, it is unrealistic to expect all audit reports to be issued on time, but good metrics would be to have >95% of all final audit reports delivered within 5 days of the original due date and to ensure that no report is issued >30 days beyond its original due date.

Annual Performance Metric: >95% of final audit reports delivered within 5 days of due date; no report issued >30 days beyond its original due date.

Figure 1

4. Audit Reports of High Quality

An exceptional audit can be completely compromised by a poorly crafted and poorly written audit report. Reports must be of exceptional quality in order to both protect the integrity of the program and to assure that the true meaning of the findings and observations are understood by those who have to implement the corrective actions. In most organizations, audit reports receive one or more peer reviews. However, there often is no formal, overall quality assurance program for the audit reports, and there should be one.

As an example of how a report quality assurance program could be conducted, one Fortune 100 company reviewed 10% of its audit reports each year in a two-day meeting with three to four independent peer reviewers. Given that the company conducts 600 audits annually, this meant that 60 reports were reviewed annually, proportionally distributed among all international locations. Each report was shown on a screen and the reviewers spent about 15 to 20 minutes reviewing the report’s key elements and then assigned an overall score. The process took about two to two-and-a-half days of effort but the results proved to be quite valuable in improving report quality in subsequent years. The following ten criteria were used consistently in the evaluations over a five year period:

- Timeliness – Was the report submitted on time? If late, how late?

- Team Identified – Was the audit team identified in the report?

- Audit Background – Did the report include a facility description, audit scope, date, and duration of audit? Was sufficient background information provided?

- Executive Summary – Was an executive summary included? Was it concise (e.g., one to two pages) and focused on the right issues?

- Protocols Used – Did the report describe the audit protocols that were used by the team? Did the protocols cover company requirements and applicable federal, state, regional, and local requirements?

- Findings Descriptions – Were the findings well written and to the point? Did they accurately describe the actual deficiency?

- Findings Citations – For findings based on a deviation from corporate standards or regulations were the appropriate citations provided?

- Findings Types – Were the findings appropriately classified as regulatory, company standard, or other finding type? Did each classification make sense?

- Findings Risk Levels – Were the assigned risk levels for each finding appropriate based on the written description?

- Recommendations – Did the recommendations flow logically from the findings’ descriptions? Was there a focus on both corrective and preventive actions?

For the evaluations, the criteria were entered onto the form shown in Table 3 below. The normalized score ranges from zero to 4.0 for each report; a scoring system that most people can relate to quite easily. This is a process that could be readily adapted in other organizations.

Annual Performance Metric: >90% of reports receive a score of >3.0 on a scale of 0 to 4.0.

Table 3: Audit Report Scoring Protocol

5. Strong Customer Feedback

Many companies will solicit formal feedback from site managers and staff at the completion of an audit. This is usually accomplished using a site evaluation questionnaire. There are any number of sources where auditor evaluations are provided.[v] In general, the evaluation of an audit team should focus on the factors provided below.

Was the team:

- Accurate. The findings and observations were based on an accurate interpretation of corporate standards, government regulations, or generally accepted practices (e.g., ISO 14001 Environmental Management Standard) applicable to the site and not on an auditor’s opinion.

- Thorough. The audit team was thorough in assessing the site against a pre-defined audit scope. Appropriate interviews were conducted; all pertinent documents were reviewed; and there was a comprehensive inspection of the site’s operations.

- Reasonable. The audit team interpreted the applicable requirements in a reasonable way. The expectations from interviews with site staff, especially operations and maintenance personnel, were sensible and thoughtful.

- Supportive. The team’s attitude was “how can we make the site better?” as opposed to “the more findings the better we look.”

Soliciting feedback from the audit program’s “customer” base is generally a good thing. However, certain cautions must be taken in interpreting the results. In the case of an audit, the customer is not always right. Although that goes against the general tenet in retail operations, there are cases on audits where the site is, frankly, angry at the outcome and the questionnaire results reflect that. This does not necessarily mean that it was a poor audit. It could very well mean that the site’s compliance performance was abysmal and the audit team’s results simply reflected that fact. On the other hand, an exceptionally good score on an evaluation questionnaire could mean that the audit team was “soft” in its evaluation and not that the site’s performance was outstanding.

With the above factors in mind, a good performance metric for customer feedback would be for >80% of the audits to receive a score of >90 on a scale of 1 to 100. This allows a performance cushion for those low-scoring outliers discussed above. That is not to say that the completed questionnaires reflecting poor performance should be discounted or even ignored. Each and every one of them should be independently investigated more fully to determine the root cause of the poor results. Similarly, where one particular team or team leader receives consistently exceptional scores, this too should be evaluated. The performance might turn out too indeed be exceptional but there might be other reasons for the high scores. Taking this critical a review of the questionnaire outcomes could be deemed unnecessarily suspicious behavior, but it is worth the effort to assure that all audit teams are conducting in-depth, objective audits.

Annual Performance Metric: >80% of audits receive a score of >90 on a scale of 1 to 100.

Facility Performance KPI’s

The results of the audits are an important second component for evaluating an audit program’s performance. Three particular KPI’s can help in assessing the audit program’s effectiveness at the facility level. They include evaluating (1) the number of high priority findings per site, (2) the number of repeat findings per site, and (3) the on-time closure of action items.[vi]

1. Number of High Priority Findings per Site

Many companies rank individual audit findings by the level of risk posed to the organization. In these cases a three-tiered classification system is often used, which essentially classifies each finding as high, medium, or low risk; significant, major, or minor; or even level I, II, or III. Regardless of what the levels are called, each risk level will have a specific definition that the auditors must use in assigning a level. For example, a significant finding might be defined as a situation that could result in substantial risk to the environment, the public, employees, stockholders, customers, the company or its reputation, or in criminal or civil liability for knowing violations. These top-tier findings are obviously critical deficiencies and as such deserve to be monitored by the company. Thus, one potential metric for an audit program would be the average number of high-risk findings identified on the audits.

Unfortunately, even with well-articulated definitions such as the one provided above there is often a lack of consistency in applying a ratings scheme, leaving some to question the merits of using this metric. Some of the reasons for inconsistency include:

- No matter how well vetted within the organization, the definitions always leave room for interpretation.

- For many safety findings extrapolated to a worst case scenario, the risk could always be interpreted as high or significant.

- Some but not all auditors believe that no regulatory finding could possibly be minor.

- Some but not all auditors (and at times legal counsel) believe that all regulatory findings should be classified as significant.

Notwithstanding these legitimate concerns, tracking the highest risk findings makes some logical sense. A candidate metric might be to have a goal of <10% of the overall findings classified as significant. Then over time, one could ratchet this goal down to <5%. Although, as stated previously in this article, ratcheting down metrics over time comes with its own set of concerns and challenges.

It should be noted that some companies do not classify findings based on risk, believing that all findings are equally important. Although this appears counter-intuitive to most experienced auditors (e.g., there is a difference between a missing machine guard on a critical piece of equipment versus an outdated safety data sheet for a seldom-used water treatment chemical), for these companies, this metric is obviously not appropriate.

Annual Performance Metric: <10% of findings are high priority findings, on average.

2. Number of Repeat Findings per Site

Many corporate audit programs are designed to capture and report on repeat findings on individual facility audits. A repeat finding can be defined as:

- A finding that had been identified in the previous independent audit of the same topic (e.g., environmental, employee safety) for which a corrective action has not been completed; or

- A finding of a substantially similar nature to one that had been identified, and reportedly corrected, in the previous independent audit of the same topic.

These repeat findings are typically considered serious and justifiably receive significant management attention. In one case, a Fortune 500 company established a requirement that no more than 2% of the findings on any audit could be repeat findings. Otherwise, the annual bonus of that business unit’s managing executive would be adversely affected. The subsequent experience in using this metric proved a cautionary tale as sites would argue incessantly with the auditors on an audit if and when they began approaching the 2% threshold. The root of the problem turned out to be that the company had never clearly defined a “repeat finding” and relied on the auditors’ discretion to make the call. This resulted in widely divergent interpretations and a chaotic environment.

Thus, the main problem with using repeat findings as a valid metric for measuring performance is that most companies have not gone to the trouble of defining what is and what is not a repeat finding. As discussed in a previous article[vii], there is a way to define repeat findings so that the classification is meaningful and consistently understood across the organization. A repeat finding should first be material and second should result from a breakdown in a management system or operational control as opposed to “one-offs” that occur routinely at sites, even those sites that are extremely well managed. For example, where there is a guard missing from a critical piece of equipment and this is observed on two consecutive audits, this should be classified as a repeat finding. It is a material issue and there is a clear lack of institutional control. Alternatively, there are any number of observations that can be made on consecutive audits that might not be material or represent a breakdown in management systems or controls. They are simply these recurring one-offs that are endemic to large complex operations. Examples might include:

- Occasional exceedances of pH limits in the site’s permitted wastewater discharge

- One of several hundred portable fire extinguishers with a missing monthly inspection tag

- A hazardous waste manifest with some minor discrepancies

- One Safety Data Sheet (SDS) for a seldom used chemical that is five years old.

It just wouldn’t seem fair to punish a site through a repeat finding process for the above deficiencies. Yes, the site should always work to get better but realistically these types of issues will periodically recur regardless of how well a management system is implemented.

Also, where a previous finding has not been corrected, the auditor should be cautious about classifying this as a repeat in all cases. For example, assume that an audit team determined that a facility required a certain regulatory permit that it did not currently have and that this resulted in a finding. On the subsequent audit, it was determined that the site still did not have the permit but had done everything in its power to procure it, which included submitting an application to the applicable agency, responding to formal comments from the agency, meeting with key agency staff, and so on. The permit application and its issuance were simply hung up in the agency’s bureaucracy. This clearly remains an important issue for the site but would typically not be classified as a repeat finding on the second audit as the situation was not identical to that observed on the first audit. Significant progress had been made. On the other hand, had the site simply ignored the initial finding and taken no action to procure the permit then that would more clearly be a repeat finding.

In summary, repeat findings observed on audits are a valid and important metric for an audit program. A good target might be to require <3% of all findings be repeat findings on average. However, this target can only work and survive within the organization if the audit program defines repeat findings precisely and if this definition does not unduly punish a site whose operations are well managed.

Annual Performance Metric: <3% of findings are repeat findings, on average.

3. On-Time Closure of Action Items

Any audit results in a corrective action plan, usually developed by the management of the site that was audited. The plan includes: a description of the finding, the proposed corrective action, the person responsible, and the target date for completion. Many companies formally track the closure of these action items and calculate the percentage of those that are completed on time. It’s all about “Say what you do; and do what you say.” This metric can be very useful in determining the value of and commitment to an audit program. Its benefits are:

- It’s a simple measurement.

- The responsible individuals are the one’s defining the actions and setting the dates.

- It’s a true measure of management’s commitment to compliance.

- Using a percent closure metric normalizes performance among differing operations.

Even with this metric, there are challenges. Some of those observed in companies that use this as a metric include:

- The numerator and denominator of the ratio (i.e., action items closed on time to total action items) should be clearly defined and reported consistently.

- Complete 100% on-time closure is unrealistic and should be challenged.

- Original timelines need a sanity check; there is a tendency to revise/extend dates when being tracked.

- Original target dates need to be fixed; unless an extension is reviewed and approved by a senior executive.

On-time closure of action items is probably one of the best, if not the best, metrics for an audit program. It demonstrates that the sites and the organization as a whole take the results of the audit program very seriously. That being said, a 100% on-time closure rate is unrealistic and would not be an appropriate target. A good, valid metric would be >90% closure of all action items on average. A secondary metric could be no action items closed beyond twice their assigned time period. This would track any outliers that are hidden by the 90% metric.

Annual Performance Metric: >90% on-time closure of audit action items. No action items closed beyond twice their assigned time period.

Conclusion

Audit programs have become an essential component of most organizations’ EHS management systems and controls. As such, they need to be well understood by all participants and stakeholders and should be regularly evaluated against established goals and objectives. This evaluation needs to be more than simply counting and tracking the total number of findings on individual audits. There are any number of other key performance indicators that should drive the management and results of a program. These KPI’s should be well thought out and implemented in a way that improves both the performance of the program and the sites that are audited.

About the Author

Lawrence B. Cahill, CPEA (Master Certification) is a Technical Director with Environmental Resources Management (ERM) and has over 35 years of professional EHS experience with industry and consulting. He is the editor and principal author of the widely used text, Environmental, Health and Safety Audits, 9th Edition and its 2015 follow-up text EHS Audits: A Compendium of Thoughts and Trends, both published by Bernan Press. He has published over 70 articles and has been quoted in numerous publications including the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Mr. Cahill has worked in more than 25 countries during his career. He holds a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from Northeastern University, where he was elected to Pi Tau Sigma, the International Mechanical Engineering Honor Society. He also holds an M.S. in Environmental Health Engineering from the McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science of Northwestern University, and an MBA from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Article Notes

[i] Cahill, L.B., “Measuring the Success of an EHS Audit Program,” EHS Journal On-Line, August 23, 2010.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] ISO 19011:2011, Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems, Section 7.2.2.

[iv] Cahill, L.B. and R.J. Costello, “Classic Auditor Failures,” EHS Journal On-Line, June 30, 2012.

[v] See: Cahill, L.B., “Environmental, Health and Safety Audits,” 9th edition, Government Institutes Division, an Imprint of The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, MD, 2011, Appendix K, Page 639, Model Audit Appraisal Questionnaire.

[vi] Much of the discussion in the Facility Performance KPI Section is drawn from “Measuring the Success of an EHS Audit Program,” published by the author and cited in endnote “i” above.

[vii] Cahill, L.B. and R.J. Costello, “Repeat vs. Recurring Findings on EHS Audits,” EHS Journal On-Line, March 31, 2012.

References

For more information on this topic, please consult the following references:

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), “Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems (ISO 19011:2011)”, 2011.

- Board of Environmental, Health and Safety Auditor Certifications (BEAC), “Standards for the Professional Practice of EHS Auditing”, 2008.

- ASTM International, “Standard Practice for Environmental Regulatory Compliance Audits (E2107-06)”, 2006.

- Cahill, L.B., Environmental, Health and Safety Audits: A Compendium of Thoughts and Trends, Bernan Press, Lanham, MD, Summer 2015.

- Cahill, L.B., Editor and Principal Author, Environmental, Health and Safety Audits, Government Institutes Division, an Imprint of The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, MD, 1983-2011.

- Cahill, L.B. and R.J. Costello, “Classic Auditor Failures,” EHS Journal On-Line, June 30, 2012.

- Cahill, L.B. and R.J. Costello, “Repeat vs. Recurring Findings on EHS Audits,” EHS Journal On-Line, March 31, 2012.

- Cahill, L.B., “Using Risk Factors to Determine EHS Audit Frequency,” EHS Journal On-Line, April 23, 2011.

- Cahill, L.B., “Measuring the Success of an EHS Audit Program,” EHS Journal On-Line, August 23, 2010.

Photograph: Curves by Flitcroft, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A.